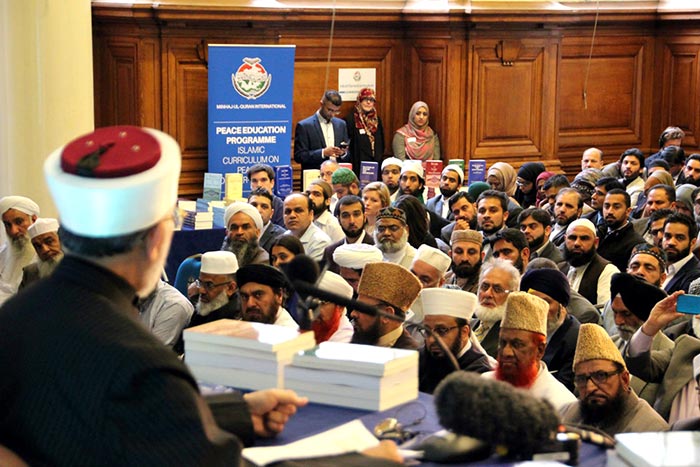

On the 23rd of June, Shaykh-ul-Islam Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri delivered his keynote speech during the official launch of the Islamic Curriculum on Peace and Counterterrorism. In attendance were official guests, including Baroness Sayeeda Warsi, Brigadier Paul Harkness, Khalid Mahmood MP, along with eminent Islamic scholars from around the UK.

The audience, consisting of academics, researchers, educationalists, head teachers, Prevent officers, police and custodial services and over a hundred Muslim imams and scholars, listened attentively while Dr Qadri explained the phenomenon of extremism, and its ideological and theological underpinnings. He explained how this new curriculum will be used to counter the extremist narrative, and his vision for it to be taught in mosque schools, seminaries and weekend religious schools, along with mainstream schools, to both Muslim and non-Muslim children.

The guest speakers were extremely appreciative and supportive of this initiative, which is part of the Peace Education Programme of Minhaj-ul-Quran International, to not only help eradicate religious extremism, but to help bring peace to society as well as community cohesion. Many of the imams and clerics committed to using the curriculum in their mosques and seminaries, while schools have requested our workers to conduct assemblies and workshops to their students. We have explained in detail below, the background and reasons for the production of this Curriculum, but if you require any further information, please email PEP@minhajuk.org

Terrorism and the spotlight on Muslims

It is an unfortunate fact that through the actions of a minority, Islam and Muslims have become closely associated with terrorism, and indeed almost synonymous with the term. This is certainly a problem for the vast majority of law-abiding Muslims themselves who feel their religion has been tarnished by the actions of a few. However, the issue has also put Muslim citizens or residents of Western countries under increased scrutiny, with questions being raised about identity, multiculturalism, and loyalty to the state. Many British people, as one prominent UK politician has controversially suggested, suspect that at least some sections of the Muslim community are a ‘fifth column’ in their midst. All these have major implications for community relations and cohesion.

The emergence of ISIS and fears of radicalisation of young Muslims

One alarming development throwing these issues into the spotlight has been the emergence of ISIS, a particularly brutal and bloodthirsty incarnation of Islamic extremism, and what appears to be a growing number of young Muslims, citizens of Western countries, travelling to the Middle East to join the organisation. Muslims travelling abroad to fight what they see as Jihad is not entirely a new phenomenon, but the brutal violence and beheadings committed by British citizens with a blatant disregard for human values has certainly heightened public awareness of Muslims and the issue of extremism.

Tackling the roots

There has been a lot of debate about the causes of radicalisation in young people, and successive governments have tried with questionable success, through well-funded initiatives and projects, to tackle the problem. The outcomes of these measures remains unclear, and the question remains whether these schemes have clearly been able to identify the underlying roots of the problem and if they are equipped with the necessary tools and knowhow to help eradicate the problem. What is clear is that the underlying causes of radicalisation are manifold and therefore the solution has to be multifaceted and all sections of society need to play their part in tackling the issues, both Muslim and non-Muslim.

Whose responsibility?

The vast majority of Muslims are peaceful and law-abiding citizens who make significant economic, cultural and political contributions to Britain, and who also endeavour in the most part to counter extremist narratives. However, there remains a feeling among a minority perhaps that the ultimate responsibility for dealing with the problem of radicalisation lies with the government and its agencies and security services. This, in our view, is a negation of responsibility, for surely parents, imams and religious teachers must be key players in the struggle against radicalisation, particularly as the method used by those who radicalise involves presenting Islamic teachings in a distorted way, or employing clichés masquerading as authentic Islamic teachings.

Recognising & countering radicalisation

It is surely the Imams of the community, the religious teachers, clerics and parents whose care children are entrusted under, and it is they who must be ultimately responsible for nurturing and educating children to ensure they are immunised against the propaganda by so-called scholars or preachers they may come across, whether in their educational institutes, mosques, clubs and societies, informal networks of friends or whether online on social media. It is, however, a cause for concern that many sections or members of the Muslim community, let alone non-Muslims, often seem to have a poor understanding of the signs of radical ideology, and how to counter radical ideas with evidence-based argument from the Qur’an and Sunnah, the primary sources of knowledge and laws of Islam, and classical scholarship. This is the reason why any strategy to effectively deal with the problem needs to focus on providing awareness not only to the young people, but also to imams, religious teachers and parents.

On the other side of the coin, it is not an exaggeration to say that most young Muslims have a very poor understanding of their religion, the methodology of interpretation, the contextualisation of passages from the Quran or Hadith, the formulation of laws, and indeed no knowledge of Arabic, the working language of law-making in Islam, sciences which have been laid down by generations of traditional Islamic scholars. Any person who is able to quote any scriptural references to a naïve young person in Arabic will be given disproportionate significance, which, added to other factors, can lead towards the path of misguidance and vulnerability to radicalisation.

Theological and ideological justifications

It should be said here that among the many causes of radicalisation and terrorism the role of theology cannot be understated. Some people, unfortunately through either genuine ignorance or for other less genuine reasons, try to deflect the blame for religious radicalisation entirely to foreign policy and military ventures in the Middle East and elsewhere. While these issues no doubt play a significant role in the process of radicalisation, too often the theologically-based narratives which underpin the ideology of the extremists are downplayed or underestimated. Radical ideology depends upon a framework of (distorted) theological reference points and scriptural justifications. It is here that appropriate intervention can bear fruit. It is important for all stakeholders concerned busy in tackling the problem to be aware of the ideological, theological and scriptural foundations of extremism and the terrible and violent acts it spawns. Challenging the narratives and belief structures with proper Islamic principles and validated interpretations of scripture must be incorporated into any method if it is to be effective.

The Islamic Curriculum on Peace and Counter-terrorism

It is with this in mind that the Islamic Curriculum on Peace and Counter-terrorism has been prepared. It has been compiled under the close personal supervision and guidance of Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri. It is separated into two volumes, one meant for young people and students, and the other for Imams, clerics and teachers, although much of the material overlaps.

As the reader will see when studying the full texts, the headings describe the main theological themes relevant to challenging radical belief, and each heading is followed by an extensive list of references from the Qur’an, hadith and other texts and resources containing relevant material. In order to increase its content and scope, but keep it to a reasonable length, only the references rather than textual quotes have been included. Some explanatory text and scriptural quotes have been included in some parts where needed.

Among the references are included a number of books by Dr Tahir-ul-Qadri that have been published for the purpose of accompanying the course books to the curriculum. The curriculum is to be used as the basis for educating and training imams, clerics, teachers and young people on the broad array of ideological and theological principles that underpin radicalisation and what the true Islamic teachings are on each subject.

It is hoped that that courses can be developed for the target audiences. Minhaj-ul-Quran International has already developed teams of people and materials to deliver talks at school assemblies and hold workshops at universities countrywide, and a schedule for these is included elsewhere in this booklet. 50 young activists have already been undergoing training to propagate the programme.

We pray and hope you will wholeheartedly support this crucial project to eradicate this plague of extremism, which is devastating families and communities, causing divisions and disharmony, and to help bring peace to society and the world.

Comments